Philosophical

Excerpt from The Good State: On Political and Constitutional Morality

In discussing the principles that should underlie a democratic constitution, two classes of consideration invite attention: those that concern the institutions of the democratic order, and those that concern the practices and personnel of the democratic order.

On the institutional side of the question, the most important points relate to the separation of functions and powers among executive, legislature and judiciary; the nature of the institutions whose purpose is the exercise of these functions and powers; the duties, extent and limits of the functions and powers of each branch and the people who operate it, and the manner and form of the definition of these functions and powers; the system of representation; and the rights of citizens, together with the remedies for any violation of their rights.

Underlying all this are crucial questions about the purpose of government and what this entails for each of these matters, and the principles that underlie the constitutional provisions for each of them.

On the side of the question relating to practices and personnel of the democratic order, the most important points relate to politicians and the nature of Party politics, the traditions and non-constitutional practices of the legislative and executive arms, Party political activity outside the legislative and executive institutions, and the press and other media.

I shall call the institutional side of the question the formal side, and the ‘people and practices’ side the informal side.

It will be seen that there are serious conflicts between the two sides of the question, as well as serious problems internal to each. This point is significant because it warns us that a constitution – even a clear, consistent, principled and detailed one that defines the duties, extent and limits of government and how it is to be carried out in the interests of the state and its citizens – is not by itself a guarantee that those interests will be served. There are many countries in the world with excellent formal constitutions which are not observed in practice, because their high-sounding intentions are ignored or subverted as a result of what happens on the informal side of the question. Tom Paine’s Rights of Man exemplifies the over-optimism of one who reposed too much confidence in the mere existence of a constitution: the course of the French Revolution, and especially the Terror of 1793-4, taught him painful lessons. The contrast between the constitutions of today’s People’s Republic of China and Russian Federation and the activities of their governments and security services offer contemporary edifying examples. Many more could be cited.

But a clear, consistent and principled constitution is a necessity nevertheless. At the beginning of Book 2 of Ab Urbe Condita Livy says that the ending of kingly rule, achieved by expelling the Tarquins, enabled ‘the authority of the law to be exalted above that of men’ in the Roman republic thus instituted. By ‘law’ in this context Livy meant a constitutional framework; laws as such are not invariably instruments of justice, and indeed can be oppressive and unjust (think ‘apartheid laws’ in South Africa, ‘Nuremberg Laws’ and other legal disabilities of Jews in Nazi Germany). But given that it is a constitution-forming legal order which, along with other conventions and traditions, governs the institutions and practices of a state, the crucial question becomes: what is a good constitution? What principles should govern its formulation and application, and how are they in turn to be justified?

The idea of the ‘authority of law above that of men’ in Livy’s sense encapsulates the purpose of a constitution, which is to define and therefore limit the competencies of those entrusted with the exercise of legislative and executive powers. In an absolute monarchy there are no such constraints; that is what ‘absolute’ means, and it therefore further means ‘arbitrary’ and ‘unrestrained’ – though even defenders of absolutism such as Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, apologist for the rule of Louis XIV of France, sought to temper absolutism by appeal to the idea that a monarch remains answerable to something putatively higher: to moral principles, or a deity.[1] In practice throughout history, as the sufferings of too much of humanity testify, such appeals have been less than universally successful. An important part of the reason is captured in Lord Acton’s dictum, ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’ But we tend to overlook the significance of the first part of that dictum: ‘power tends to corrupt’: it is not only absolute power that does so. Hence the importance of constitutional restraints; and hence the uncomfortable fact that even excellent constitutions can be nullified by what happens on the informal side of politics and government.

This is where a thought prompted by John Stuart Mill becomes relevant. In his book Considerations on Representative Government (1861) he invoked, more or less in passing, the idea of ‘constitutional morality’ as what restrains honourable men (in his day, and despite his protests, it was of course only men – apart from Queen Victoria; and then somewhat notionally – who engaged in politics and government) from bending or manipulating, for partisan or injurious purposes, the conventions, traditions and provisions of the constitutional order, then as now in the UK an uncodified one.[2] There is an echo in this of Voltaire’s remark about the England of the preceding century, where he had lived for some years in exile, namely, that its liberties were the result ‘not of the constitution (governmental arrangements) of the country but the constitution (character) of the people’ – that is, the people’s robust insistence on the inviolability of their persons and homes. Mill took it, in nineteenth century style, that it was the principles of gentlemanly behaviour that prevented governments from exercising through Parliament what were in fact – and which in the UK remain today – absolute powers.

But this is a very tenuous way of constraining what governments and their ministers can do, unhappily made obvious when the legislature and government offices come to be populated by less honourable and principled people, controlled by party machines whose influence over representatives, exercised by promises and threats relating to the representatives’ careers, is great. This is now the case; and certain events of recent years (signal examples are the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency of the US and ‘Brexit’ in the UK) are serious symptoms of failure in a system which has too long relied overmuch on self-imposed restraint and personal principles on the informal side of the question.

The fallacy in hoping that the people who populate and operate a democracy’s institutions will not abuse the latitude for action they find in them is stingingly illustrated by Han Fei’s story of the farmer and the hare. The story is that a farmer was ploughing a field in the middle of which stood a tree. Suddenly a hare came racing through the field, collided with the tree, broke its neck and died. The farmer so enjoyed eating the hare that he thereafter set aside his plough and sat by the tree to wait for another hare to come along and break its neck. Han Fei, one of the leading Legalist philosophers of the Warring States period in ancient China (third century BCE), drew the moral: the folly of doing the same in hopes that another sage king would appear speaks for itself. His view that government must be a matter of law-governed institutions rather than the happenstance of talent or good character in individual people finds its echo in Livy several centuries later.[3]

An appeal to ‘constitutional morality’ as what politicians will observe in legislating and governing is therefore no longer good enough, if it ever was. The formal side of the question has to address this problem by imposing a far clearer set of requirements on those who occupy the institutions and offices of state. But because it can never obviate the potential problems that arise on the informal side, there has to be renewed effort to create a climate in which the informal side is less susceptible to the corrosive influences to which by its very nature it is prey.

These are the great questions, both formal and informal, discussed in Grayling A. C. The Good State: On Political and Constitutional Morality (London: Oneworld) forthcoming 2019.

[1] Bossuet Politics Derived from the Words of Holy Scripture (1709). ‘But kings, although their power comes from on high, as has been said, should not regard themselves as masters of that power to use it at their pleasure…they must employ it with fear and self-restraint, as a thing coming from God and of which God will demand an account.’

[2] Mill op cit ch 5

[3] Han Fei Han Feizi ref To quote Han Fei’s story of the hare is not to approve everything in his views, as will appear later.

Legal

Why the law should protect “true” vegans

Something very good happened at the beginning of this decade.

On the 3rd of January 2020, Employment Judge Robin Postle ruled in Norwich Employment Tribunal that ethical veganism is now a protected philosophical belief under the Equality Act 2010. The news of this judgment circulated all over the world in such an unprecedented fashion, than in three weeks they could be read in more than 1,200 websites from more than 60 countries.

Why? you may ask. Why people in Lebanon, Indonesia, Qatar or Peru are so interested in what happened in Norwich (while they may never heard the name of this Norfolk city before)?

The reason is simple. This was a “landmark decision” of international proportions. Arguably, veganism is one of today’s fastest growing international social movements, but yet it has not reached the “policy” stage yet anywhere in the world…until now. The Norwich judgment is the first of this kind in the world, and it does not refer only to my particular belief (as I am the Claimant who brought that case), or the belief of the English vegans, but to the concept of ethical veganism in general, which is essentially the “original” concept of veganism, as defined by The Vegan Society when it was formed in 1944. Therefore, if it is recognised in Great Britain as a belief which deserve as much protection as any other protected belief, religious or otherwise, surely it should be recognised elsewhere as well, as ethical veganism is the same anywhere (it doesn’t change with different cultural backgrounds), discrimination can occur anywhere, and anti-discrimination legislation should exist everywhere (although it doesn’t yet).

This judgment doesn’t change the law, or creates an actual new legal precedent, but what it does is legally recognises that when the Equality Act 2010 was enacted, and it protected non-religious philosophical beliefs as much as religions, it implicitly included among many the belief of ethical veganism, as this passes the test created by the Employment Appeals Tribunal in 2009. This test, coming from the Grainger plc v Nicholson case, created the following requirements a judge must confirm a non-religious belief has to fulfil to be protected under the act:

- the belief must be genuinely held;

- it must be a belief and not an opinion or viewpoint based on the present state of information available;

- it must be a belief as to a weighty and substantial aspect of human life and behaviour;

- it must attain a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance; and

- it must be worthy of respect in a democratic society, not be incompatible with human dignity and not conflict with the fundamental rights of others.

Judge Postle did confirm (using the words “overwhelmingly”) that ethical veganism fulfils all this criteria, and he also confirmed that I am an ethical vegan, and therefore my discrimination case based on this belief can now continue.

It is important to notice that this doesn’t mean that all those who define themselves as vegan would now be protected from discrimination, harassment and victimisation as are those who hold other protected characteristics (such as gender, age, marital status, religion, etc.). It will only protect “true” vegans. With this I mean, for one side, those who hold the belief genuinely and not just follow a temporary fashion or only “practice” the manifestation of such belief when it’s convenient to them. And for the other side, only those who follow the Vegan Society’s definition to the full, which means aiming to exclude, when practicable and possible, all forms of animal exploitation and cruelty to animals, not only those related to food production. Therefore, those who only follow a vegan diet but still want to wear clothes with animal products (such as wool or leather) or still want to visits zoos for entertainment, those are not “ethical vegans” even if they define themselves as vegan, so they would not be protected. Is this fair? I think it is, because I think society should protect more those who change their lifestyle to help others (animals suffering or the environment being destroyed) than those who only do it for themselves (to have a better health or look younger).

Ethical veganism is growing so fast because is a positive non-religious universal philosophy that tries to solve the most important problems we have in the world today: the trillions of animals that every year suffer from being unnecessarily exploited by humans, the catastrophic destruction of the environment (including global warming) caused by the animal agriculture industry, the hunger created by the waste of land and water used to raise animals for food and clothing, the severe health problems caused by the widespread consumption of animal products, and the legitimisation of abuse, exploitation and oppression as a form of progress . A society which allows to discriminate those who try to minimise their negative impact to the world, at the same time they try to help everyone else by providing a real practical solution to the world’s worse problems, is an outdated society with no foresight.

“True” vegans need protecting because unfortunately they are already discriminated, harassed, victimised, and hated by people who are blind to the real world’s problems and who are unwilling to share their privileges with those less fortunate. Those who after millennia of indoctrination think that others don’t’ matter, only they do, are ironically not from the Selfie and YouTube generation, but from the gladiators generation, the crusades generation, the witch-hunting generation, the foxhunting generation, and the factory farming generation. These outspoken institutionalised selfish “carnists” who are so triggered by the concept of veganism are who the law should be keeping “at bay” so ethical vegans can finally manifest their beliefs to the full without fear and worry, and in so doing freely attempt to significantly improve the world for next generations to come.

Surely, that is a good thing.

Legal

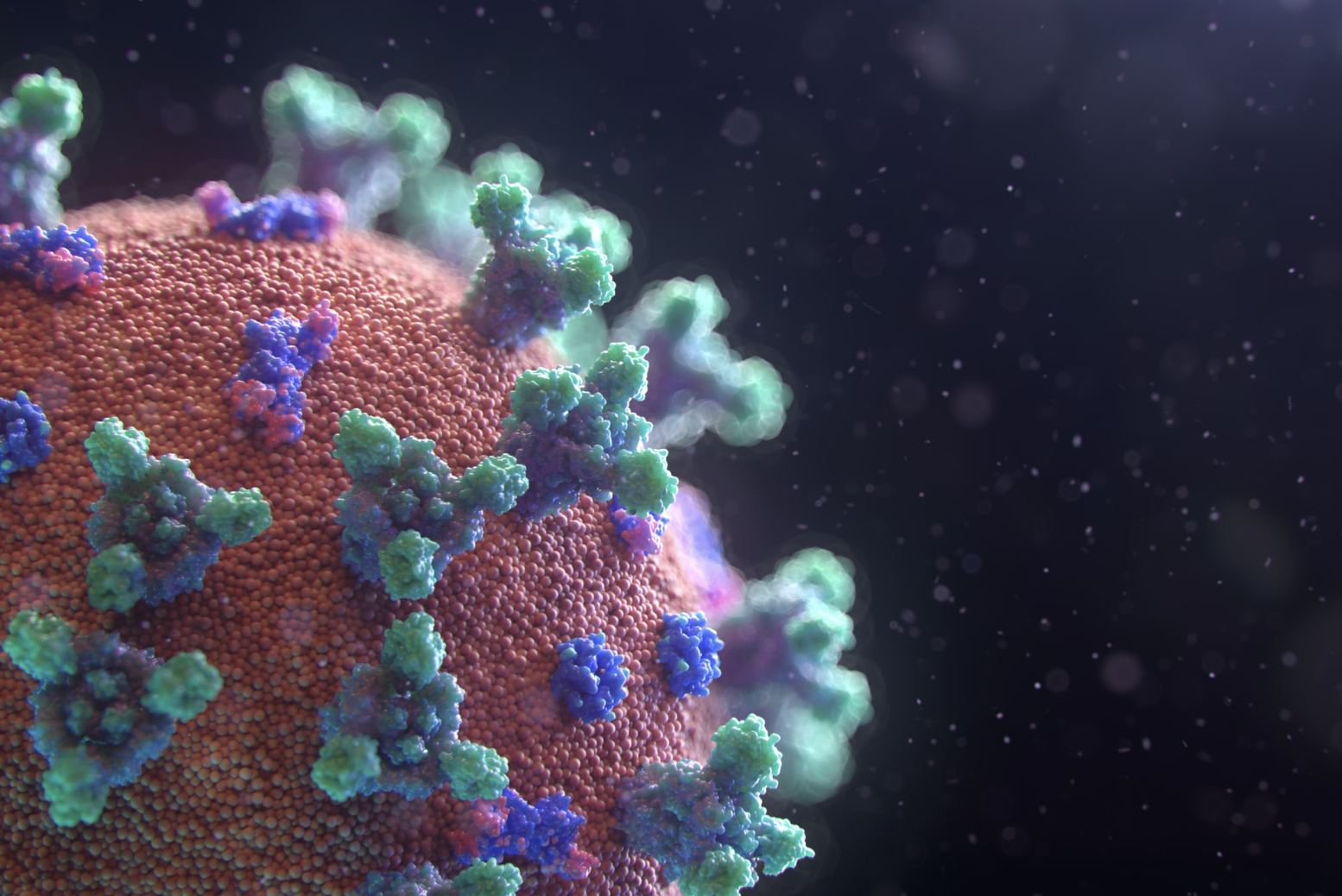

Reckless Transmission of Covid-19: A Jail Sentence?

With the death toll of the infamous coronavirus having recently surpassed 20,000, there is a real sense of fear propagating among the general public as to how best protect themselves, evidenced through the increasing sightings of shoppers kitted up in surgical masks. Just last week, a 57-year old man in Dudley, who claimed to be infected with Covid-19 and deliberately coughed at the staff in a local shop, was arrested under the Mental Health Act of 1983, which allows for someone to be ‘detained in the interests of his own health or safety or with a view to the protection of other persons’. However, during these extraordinary times, it may be interesting to consider whether the reckless transmission of Covid-19 could go beyond just detention by the police and indeed constitute a criminal offence. For, under section 20 of the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861 (OAPA), the unlawful infliction of grievous bodily harm (GBH) could result in up to seven years’ imprisonment. It must be emphasised, however, that while analysing the possible legal implications, it is important to bear in mind that the probability of possessing sufficient evidence of the transmissionof Covid-19 is highly limited.

Clearly, the first point for contention is whether Covid-19 can be said to constitute GBH, that is to say, the arguably ambiguous notion of ‘really serious’ harm established in DPP v Smith. Interestingly, it was ruled in R v Dica that this harm does not necessarily have to be a direct act of violence; the transmission of a disease, HIV in that case, could represent the causation of physical injury. As controversial as it may seem, therefore, prosecuting the unlawful transmission of disease in itself is not beyond the reach of the law. More strikingly, this harm does not have to be permanent or dangerous: it is up to the jury to decide the perceived level of harm done in reference to current societal norms. In reference to Covid-19, cynics may downplay the gravity of the harm given that the death rate lies at around 1%, but it is important to remember that this virus has the potential to befatal for some and so, in these cases, could indeed be seen as a really serious harm. As Weait convincingly argues, even if the physical harm of disease transmission is up for debate, the psychological harm of receiving a potentially life-threatening disease is one which the law ought to acknowledge. Therefore, it would be convincing to argue that, especially in cases where the affected has underlying health conditions or is in a greater threatened demographic, the transmission of Covid-19 could be viewed as a harm serious enough for the possibility of prosecution under the OAPA.

Of course, simply transmitting a disease alone is no criminal offence: just visualise that student who, the day before you picked up the flu, was sneezing incessantly at the back of the class, unpunished. More than just infecting you, it is necessary that the ‘infector’ show a degree of recklessness (the mens rea of the offence). As established in R v Parmenter, it is Cunningham (or subjective) recklessness which is applied under offences of GBH; this is the idea that the infector must have foreseen a risk of harm but decided to take the unjustified risk regardless. In relation to Covid-19, the jury would need to consider whether the actions of the defendant demonstrated such recklessness – whether that be, inter alia, through failure to self-isolate or, more overtly, unrestrained coughing directly at the victim. Undoubtedly, this concept of ‘recklessness’ is ambiguous and thus some feel that to criminalise this area is an example of the unnecessary pervasiveness of the criminal law, believing that only through greater education can we effectively reduce disease transmission. Moreover, it is almost impossible to ascertain what level of precaution would be needed to mitigate recklessness. Consider whether the defendant wearing a mask, as almost universally deemed ineffective by the WHO, would be sufficient. While this article aims neither to advocate nor oppose the criminalisation of disease transmission and acknowledges the uncertainty around the meaning of ‘recklessness’, it may theoretically be found that reckless transmission of Covid-19 could be within the grasp of the criminal law.

Nevertheless, in order to be reckless as to the transmission of the coronavirus, the infector would need to have relevant knowledge of their status. With access to satisfactory testing restricted and many being advised to simply stay at home if they display symptoms, it is often very difficult to know for certain whether you are infected. Hence, in order to be liable for reckless transmission, it is likely that your relevant knowledge would need to be a positive diagnosis with the virus. Having said that, the idea of requiring clear, incontrovertible knowledge is not universally accepted: Sullivan argues that wilful blindness could equivalate to actual knowledge, that is to say that if you were aware that it was very likely that you had the virus but decided nonetheless to behave in a reckless manner, then you could be liable. Although there is not concrete evidence of how a court would react in this scenario, in the unreported case of R v Adaye where a man was told by a doctor that it was very likely that he had HIV but refused to be tested, the court ruled that he could still be deemed as possessing the relevant knowledge. However, as argued by Ryan, this could result in unjust criminalisation given that the line between wilful blindness and actual knowledge can sometimes be very blurred. More relevantly, unlike with many of the prosecutions for the transmission of STDs, it has been suggested that some may have the coronavirus yet show no symptoms during the ‘incubation period’ or may even never know that they were infected. As you can see, it would be an uphill task trying to prove that the defendant knew of their status unless they had been positively tested. As a result, it would be naïve to suggest that you could be found liable for recklessly transmitting Covid-19 unless you positively knew of your status.

So, can I be prosecuted for transmitting Covid-19? Well, the law is not clear. While this article demonstrates that you could theoretically be prosecuted if you knowingly and recklessly transmitted the disease, it is not plausible to suggest that you would actually end up in jail. To prove that it was you who transmitted the disease, and not one of the other thousands infected, would be impractical and costly and so the prospects of being imprisoned are clearly almost zero. However, this pandemic serves to bring back to light wider questions about whether the criminalisation of disease transmission is beneficial for public health policy. Admittedly, this article only touches the surface and omits important situations such as the relevance of whether a family member consenting to the risk of transmission could negate an infector’s liability. Nevertheless, it aims to underline the necessity for governments to assess the most effective methods to control the spreading of the coronavirus. The wider question: is the criminal law the best one?

Legal

Giving nature human rights

Amidst an era of wide and profound natural degradation, Lake Erie, situated on the US-Canadian border, last week joined the growing list of natural sites worldwide granted the legal title of Personhood.

This move is an innovative conservation measure attempting to succeed where previous, more conventional, protections have failed. As the climate crisis and ever-increasing human encroachment and pollution drag the world’s most beautiful natural sites to the brink, many see expanding the breadth of legal personhood to include natural sites as the answer.

For decades, locals have observed the deterioration of Lake Erie with a mixture of dismay and exasperation. All other attempts to regulate the surrounding industries responsible for the mass pollution of the lake have failed. Perhaps a page has finally been turned.

Rampant run off from agricultural pesticides on the banks of the Lake is the main culprit for the immense algal blooms forming in the lakes. These ever-growing blooms of algae suffocate the lake, killing its fish and plant life. Furthermore, the lake is the main source of drinking water for hundreds of thousands of people who have seen its quality get gradually worse so that today it is borderline toxic. A radical approach to tackle all this was clearly necessary.

Though the first of its kind in North America, the creative legal move has already been implemented in various areas across the globe. Chief among these is the Whanganui River in New Zealand. Ruthlessly exploited for over a century, in 2017 the New Zealand parliament voted to pass legislation conferring legal personhood on the river, declaring it an indivisible, living whole possessing “all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities” of a legal person.

This move was long-overdue in the eyes of the local Maori people who have always considered the river, the principal source of life for their community, a living being worthy of equal, if not superior, respect as a person. The decision was taken not only to protect a universal site of natural beauty and source of life but also for political reasons. It came as part of a broad governmental initiative to “atone for [the state’s] past wrongs and begin the process of healing”. In so doing, it was made clear that this was more than just a conservationist measure but also an attempt to come to terms with a brutal past filled with shameful exploitation and human atrocities.

This progressive sentiment from the New Zealand government is hugely encouraging for indigenous rights activists and environmentalists worldwide but is still a highly radical exception among the settler colonial nations. Though it is still a far-flung dream to imagine the US ever expressing such historical remorse or desire to make amends, more than ever under the current administration, the legal move at Lake Erie is nevertheless a hugely encouraging step forwards in recognising man and nature’s interconnectivity.

Gerard Albert, chairman of the Whanganui tribal collective, welcomed the “recognition that the river is the indivisible and living whole of Maori understanding and not the fragmented, inanimate components… that has been the European approach.” This touches on the belief held not only by the Maori but by many indigenous groups worldwide, of the interconnected relationship between man and nature. One of mutual respect, obligation and responsibility and one gaining more mainstream attention across the western world. Thanks to Extinction Rebellion and other climate justice movements, this quasi-animist belief is, for the first time, gaining traction in the capitalist societies of the West. The significance of this cannot be understated. It is in great part the western belief, stemming from a particular Christian biblical interpretation, that nature is man’s dominion to shape and plunder as he so wishes that has led the world to the ecological brink.

It is still to be seen whether these new legal measures will hold up when challenged. They are yet to be tested in their respective legal system and may well prove toothless again conventional legal attacks. Indeed, it is not yet known the scope of the new move. For example, will a river be able to sue a corporation polluting its water with toxic waste? As yet, no one really knows. Only time will tell the true significance but what is for sure is that affording legal Personhood to nature is an innovative move worth trying in a world that requires protection as never before.

-

Legal2 years ago

Legal2 years agoHow we can defend and protect rights in the time of Coronavirus (COVID-19)

-

Legal2 years ago

Legal2 years agoLook at Afghanistan; why human rights are inextricably linked with the rule of law

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoThe right to protest in a Covid-19 era

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoA Public Health Approach to Tackling Racism

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoA Runaway Decision? Discussing and Defending R (Plan B Earth) v Secretary of State for Transport

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoTrump: the most prolific execution President in over 130 years

-

Legal7 months ago

Legal7 months agoIs unjust enrichment really concerned with enrichments?

-

Economic3 years ago

Economic3 years agoWhat is the Rule of Law and What Difference Does it Make?