Philosophical

Is Wearing a Burkha in a Western Country as Offensive as Wearing a Bikini in an Arab Country?

To take away the burkha as an offence is to reject freedom of religion and of expression. In order to fully answer this question, one must recognise the motives behind wearing a burkha – which is Islam. A burkha is known as ‘hijab’, which means modesty, and is worn by some Muslim women who feel liberated, more comfortable, and closer to Allah wearing it. So why do certain people have certain issues with this – or more importantly, who deems what offensive? What higher power decides what is wrong, and what isn’t?

Now we must discuss what offensive means here – to cause offence is to commit an inappropriate act, or say inappropriate things causing upset, anger or frustration. It could also mean something that’s distasteful, disagreeable or unpleasant. But there is a line between offensive and illegal. In Arab countries, a bikini is not only offensive, it’s illegal. Why? The norms and values are different – one could describe them as extreme. A bikini is illegal because it clashes with the values and beliefs Islam provides and Arab countries are evidently predominantly Islamic. Many Western countries like the US have no religion that the majority of the population follow, so who does the burkha offend?

There is liberty in being able to choose to wear whatever one pleases. Let’s understand why some women choose to wear a bikini. A bikini is worn by some women who feel liberated, more comfortable and closer to themselves wearing it. There is not a particular belief as to why they should wear them, it is a choice. As is wearing a burkha. The idea of free-will is a basic human right linking to Article 10 (freedom of expression). The greater ‘offence’ would be withdrawing this right to liberty and autonomy. There is no writing in the Qu’raan that explicitly states the importance of covering a woman’s body and hair, it is a choice. As is a bikini. Let’s start by asking ourselves one question – why is one seen as oppressive, and the other as freeing? If this is the case, let’s move on and ask ourselves another question – which is oppressive, and which is freeing? It depends on the situation. In a recent volleyball match with Germany and Egypt, it was discovered that in Germany, female players were not allowed to wear anything other than a bikini, whereas Egyptian players could wear anything they felt comfortable in. The definition of oppressive is to inflict harsh and authoritarian treatment, which is evidently what Germany’s team leaders are doing, because allowing women to make a choice about what they want to wear is less offensive than infringing a certain uniform on them. Therefore, oppression is not represented by the clothing one wears, it is represented by the freedom of choice to wear such clothing.

It is important to understand what it means to wear a burkha to western society. Arab countries, like Saudi Arabia, can be oppressive. Women have only just been allowed to start driving. Perhaps the burkha is a symbol of this patriarchal society and is thus deemed offensive: oppressive and disrespectful. It could be seen as offensive to the progressive nature of women in Western societies and the ways in which they are viewed. But, surely it is more oppressive and disrespectful to ban these religious emblems? France, in 2004, banned all religious clothing in public areas in order to commit to full ‘social integration’, so that essentially, religion would not be part of one’s identity. One could say this is the same thing as Arab countries banning bikinis, or any revealing clothing and imposing their religious beliefs on others. However the key difference is that France seems to be targeting Islam with the secularisation concept they have adopted. Arab countries are not specifically discriminating anyone, or any group of people. Some would say this is an exact of Islamophobia. If religion is part of some people’s identity, and to some it is their identity, it should be recognised that to ban something that makes your religion yours is offensive. Freedom of expression and religion are basic, fundamental human rights. Article 9 of the HRA states that in such a democratic society, each individual should be able to believe what they wish provided it does not harm or affect others – like wearing a garment. Overall, certain countries like France seem to be targeting laws against Islam which is far more dangerous than Arab countries banning a bikini is not against any group in particular.

To some, this is a feminist issue regarding who gets to decide what women do with their bodies, like the abortion ban in Northern Ireland. To others, banning the burkha creates issues about insensitive motives against Islam which is far more dangerous than banning the bikini. Arguably, if the burkha is deemed offensive and banned, the government must also ban all other religious garments in order to detach itself from Islamophobic speculation. However, a world without religion is a world without expression, or identity, or autonomy – it is a democracy-free one in which it is safe to say, no one wants to live.

Legal

Why the law should protect “true” vegans

Something very good happened at the beginning of this decade.

On the 3rd of January 2020, Employment Judge Robin Postle ruled in Norwich Employment Tribunal that ethical veganism is now a protected philosophical belief under the Equality Act 2010. The news of this judgment circulated all over the world in such an unprecedented fashion, than in three weeks they could be read in more than 1,200 websites from more than 60 countries.

Why? you may ask. Why people in Lebanon, Indonesia, Qatar or Peru are so interested in what happened in Norwich (while they may never heard the name of this Norfolk city before)?

The reason is simple. This was a “landmark decision” of international proportions. Arguably, veganism is one of today’s fastest growing international social movements, but yet it has not reached the “policy” stage yet anywhere in the world…until now. The Norwich judgment is the first of this kind in the world, and it does not refer only to my particular belief (as I am the Claimant who brought that case), or the belief of the English vegans, but to the concept of ethical veganism in general, which is essentially the “original” concept of veganism, as defined by The Vegan Society when it was formed in 1944. Therefore, if it is recognised in Great Britain as a belief which deserve as much protection as any other protected belief, religious or otherwise, surely it should be recognised elsewhere as well, as ethical veganism is the same anywhere (it doesn’t change with different cultural backgrounds), discrimination can occur anywhere, and anti-discrimination legislation should exist everywhere (although it doesn’t yet).

This judgment doesn’t change the law, or creates an actual new legal precedent, but what it does is legally recognises that when the Equality Act 2010 was enacted, and it protected non-religious philosophical beliefs as much as religions, it implicitly included among many the belief of ethical veganism, as this passes the test created by the Employment Appeals Tribunal in 2009. This test, coming from the Grainger plc v Nicholson case, created the following requirements a judge must confirm a non-religious belief has to fulfil to be protected under the act:

- the belief must be genuinely held;

- it must be a belief and not an opinion or viewpoint based on the present state of information available;

- it must be a belief as to a weighty and substantial aspect of human life and behaviour;

- it must attain a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance; and

- it must be worthy of respect in a democratic society, not be incompatible with human dignity and not conflict with the fundamental rights of others.

Judge Postle did confirm (using the words “overwhelmingly”) that ethical veganism fulfils all this criteria, and he also confirmed that I am an ethical vegan, and therefore my discrimination case based on this belief can now continue.

It is important to notice that this doesn’t mean that all those who define themselves as vegan would now be protected from discrimination, harassment and victimisation as are those who hold other protected characteristics (such as gender, age, marital status, religion, etc.). It will only protect “true” vegans. With this I mean, for one side, those who hold the belief genuinely and not just follow a temporary fashion or only “practice” the manifestation of such belief when it’s convenient to them. And for the other side, only those who follow the Vegan Society’s definition to the full, which means aiming to exclude, when practicable and possible, all forms of animal exploitation and cruelty to animals, not only those related to food production. Therefore, those who only follow a vegan diet but still want to wear clothes with animal products (such as wool or leather) or still want to visits zoos for entertainment, those are not “ethical vegans” even if they define themselves as vegan, so they would not be protected. Is this fair? I think it is, because I think society should protect more those who change their lifestyle to help others (animals suffering or the environment being destroyed) than those who only do it for themselves (to have a better health or look younger).

Ethical veganism is growing so fast because is a positive non-religious universal philosophy that tries to solve the most important problems we have in the world today: the trillions of animals that every year suffer from being unnecessarily exploited by humans, the catastrophic destruction of the environment (including global warming) caused by the animal agriculture industry, the hunger created by the waste of land and water used to raise animals for food and clothing, the severe health problems caused by the widespread consumption of animal products, and the legitimisation of abuse, exploitation and oppression as a form of progress . A society which allows to discriminate those who try to minimise their negative impact to the world, at the same time they try to help everyone else by providing a real practical solution to the world’s worse problems, is an outdated society with no foresight.

“True” vegans need protecting because unfortunately they are already discriminated, harassed, victimised, and hated by people who are blind to the real world’s problems and who are unwilling to share their privileges with those less fortunate. Those who after millennia of indoctrination think that others don’t’ matter, only they do, are ironically not from the Selfie and YouTube generation, but from the gladiators generation, the crusades generation, the witch-hunting generation, the foxhunting generation, and the factory farming generation. These outspoken institutionalised selfish “carnists” who are so triggered by the concept of veganism are who the law should be keeping “at bay” so ethical vegans can finally manifest their beliefs to the full without fear and worry, and in so doing freely attempt to significantly improve the world for next generations to come.

Surely, that is a good thing.

Legal

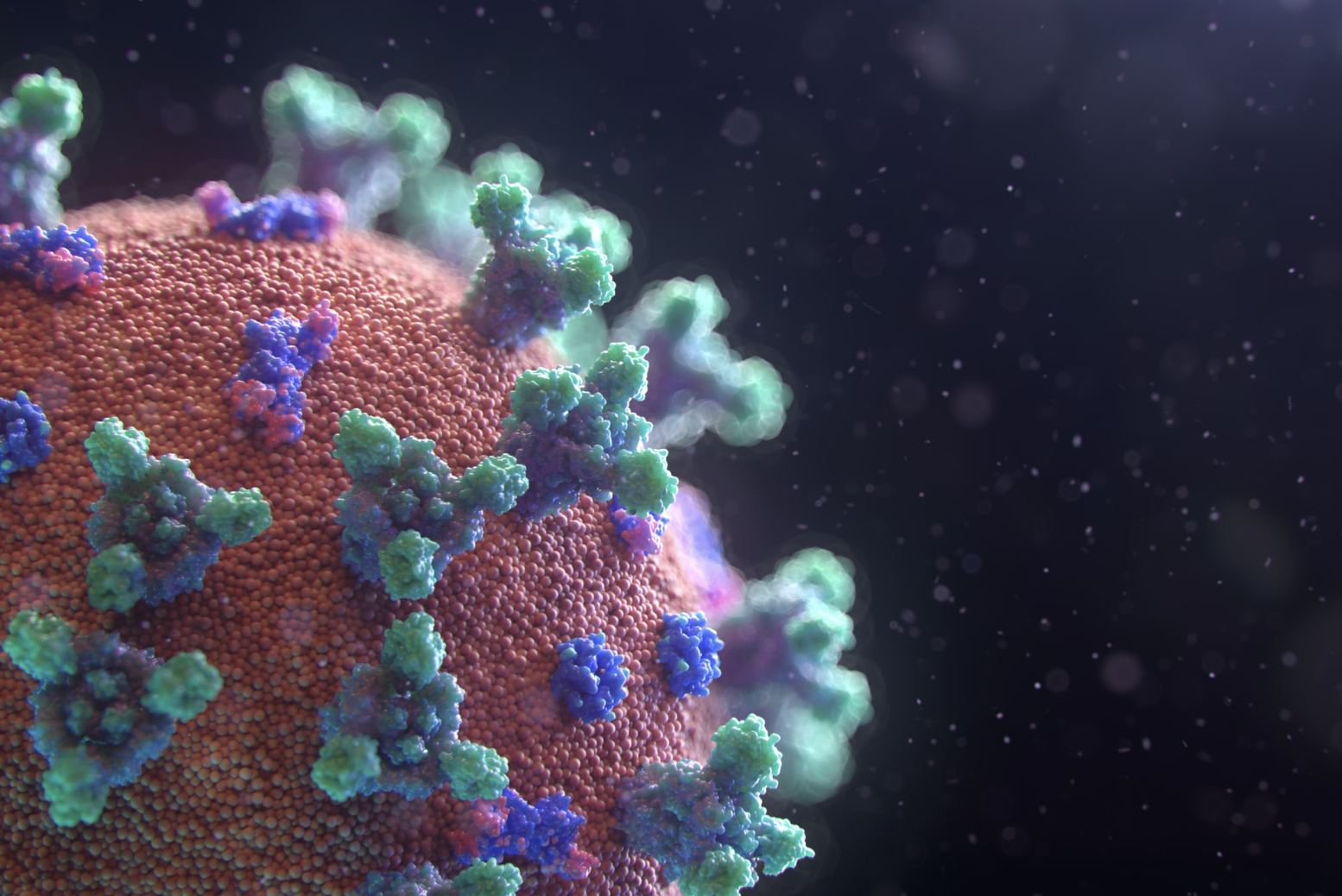

Reckless Transmission of Covid-19: A Jail Sentence?

With the death toll of the infamous coronavirus having recently surpassed 20,000, there is a real sense of fear propagating among the general public as to how best protect themselves, evidenced through the increasing sightings of shoppers kitted up in surgical masks. Just last week, a 57-year old man in Dudley, who claimed to be infected with Covid-19 and deliberately coughed at the staff in a local shop, was arrested under the Mental Health Act of 1983, which allows for someone to be ‘detained in the interests of his own health or safety or with a view to the protection of other persons’. However, during these extraordinary times, it may be interesting to consider whether the reckless transmission of Covid-19 could go beyond just detention by the police and indeed constitute a criminal offence. For, under section 20 of the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861 (OAPA), the unlawful infliction of grievous bodily harm (GBH) could result in up to seven years’ imprisonment. It must be emphasised, however, that while analysing the possible legal implications, it is important to bear in mind that the probability of possessing sufficient evidence of the transmissionof Covid-19 is highly limited.

Clearly, the first point for contention is whether Covid-19 can be said to constitute GBH, that is to say, the arguably ambiguous notion of ‘really serious’ harm established in DPP v Smith. Interestingly, it was ruled in R v Dica that this harm does not necessarily have to be a direct act of violence; the transmission of a disease, HIV in that case, could represent the causation of physical injury. As controversial as it may seem, therefore, prosecuting the unlawful transmission of disease in itself is not beyond the reach of the law. More strikingly, this harm does not have to be permanent or dangerous: it is up to the jury to decide the perceived level of harm done in reference to current societal norms. In reference to Covid-19, cynics may downplay the gravity of the harm given that the death rate lies at around 1%, but it is important to remember that this virus has the potential to befatal for some and so, in these cases, could indeed be seen as a really serious harm. As Weait convincingly argues, even if the physical harm of disease transmission is up for debate, the psychological harm of receiving a potentially life-threatening disease is one which the law ought to acknowledge. Therefore, it would be convincing to argue that, especially in cases where the affected has underlying health conditions or is in a greater threatened demographic, the transmission of Covid-19 could be viewed as a harm serious enough for the possibility of prosecution under the OAPA.

Of course, simply transmitting a disease alone is no criminal offence: just visualise that student who, the day before you picked up the flu, was sneezing incessantly at the back of the class, unpunished. More than just infecting you, it is necessary that the ‘infector’ show a degree of recklessness (the mens rea of the offence). As established in R v Parmenter, it is Cunningham (or subjective) recklessness which is applied under offences of GBH; this is the idea that the infector must have foreseen a risk of harm but decided to take the unjustified risk regardless. In relation to Covid-19, the jury would need to consider whether the actions of the defendant demonstrated such recklessness – whether that be, inter alia, through failure to self-isolate or, more overtly, unrestrained coughing directly at the victim. Undoubtedly, this concept of ‘recklessness’ is ambiguous and thus some feel that to criminalise this area is an example of the unnecessary pervasiveness of the criminal law, believing that only through greater education can we effectively reduce disease transmission. Moreover, it is almost impossible to ascertain what level of precaution would be needed to mitigate recklessness. Consider whether the defendant wearing a mask, as almost universally deemed ineffective by the WHO, would be sufficient. While this article aims neither to advocate nor oppose the criminalisation of disease transmission and acknowledges the uncertainty around the meaning of ‘recklessness’, it may theoretically be found that reckless transmission of Covid-19 could be within the grasp of the criminal law.

Nevertheless, in order to be reckless as to the transmission of the coronavirus, the infector would need to have relevant knowledge of their status. With access to satisfactory testing restricted and many being advised to simply stay at home if they display symptoms, it is often very difficult to know for certain whether you are infected. Hence, in order to be liable for reckless transmission, it is likely that your relevant knowledge would need to be a positive diagnosis with the virus. Having said that, the idea of requiring clear, incontrovertible knowledge is not universally accepted: Sullivan argues that wilful blindness could equivalate to actual knowledge, that is to say that if you were aware that it was very likely that you had the virus but decided nonetheless to behave in a reckless manner, then you could be liable. Although there is not concrete evidence of how a court would react in this scenario, in the unreported case of R v Adaye where a man was told by a doctor that it was very likely that he had HIV but refused to be tested, the court ruled that he could still be deemed as possessing the relevant knowledge. However, as argued by Ryan, this could result in unjust criminalisation given that the line between wilful blindness and actual knowledge can sometimes be very blurred. More relevantly, unlike with many of the prosecutions for the transmission of STDs, it has been suggested that some may have the coronavirus yet show no symptoms during the ‘incubation period’ or may even never know that they were infected. As you can see, it would be an uphill task trying to prove that the defendant knew of their status unless they had been positively tested. As a result, it would be naïve to suggest that you could be found liable for recklessly transmitting Covid-19 unless you positively knew of your status.

So, can I be prosecuted for transmitting Covid-19? Well, the law is not clear. While this article demonstrates that you could theoretically be prosecuted if you knowingly and recklessly transmitted the disease, it is not plausible to suggest that you would actually end up in jail. To prove that it was you who transmitted the disease, and not one of the other thousands infected, would be impractical and costly and so the prospects of being imprisoned are clearly almost zero. However, this pandemic serves to bring back to light wider questions about whether the criminalisation of disease transmission is beneficial for public health policy. Admittedly, this article only touches the surface and omits important situations such as the relevance of whether a family member consenting to the risk of transmission could negate an infector’s liability. Nevertheless, it aims to underline the necessity for governments to assess the most effective methods to control the spreading of the coronavirus. The wider question: is the criminal law the best one?

Legal

Giving nature human rights

Amidst an era of wide and profound natural degradation, Lake Erie, situated on the US-Canadian border, last week joined the growing list of natural sites worldwide granted the legal title of Personhood.

This move is an innovative conservation measure attempting to succeed where previous, more conventional, protections have failed. As the climate crisis and ever-increasing human encroachment and pollution drag the world’s most beautiful natural sites to the brink, many see expanding the breadth of legal personhood to include natural sites as the answer.

For decades, locals have observed the deterioration of Lake Erie with a mixture of dismay and exasperation. All other attempts to regulate the surrounding industries responsible for the mass pollution of the lake have failed. Perhaps a page has finally been turned.

Rampant run off from agricultural pesticides on the banks of the Lake is the main culprit for the immense algal blooms forming in the lakes. These ever-growing blooms of algae suffocate the lake, killing its fish and plant life. Furthermore, the lake is the main source of drinking water for hundreds of thousands of people who have seen its quality get gradually worse so that today it is borderline toxic. A radical approach to tackle all this was clearly necessary.

Though the first of its kind in North America, the creative legal move has already been implemented in various areas across the globe. Chief among these is the Whanganui River in New Zealand. Ruthlessly exploited for over a century, in 2017 the New Zealand parliament voted to pass legislation conferring legal personhood on the river, declaring it an indivisible, living whole possessing “all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities” of a legal person.

This move was long-overdue in the eyes of the local Maori people who have always considered the river, the principal source of life for their community, a living being worthy of equal, if not superior, respect as a person. The decision was taken not only to protect a universal site of natural beauty and source of life but also for political reasons. It came as part of a broad governmental initiative to “atone for [the state’s] past wrongs and begin the process of healing”. In so doing, it was made clear that this was more than just a conservationist measure but also an attempt to come to terms with a brutal past filled with shameful exploitation and human atrocities.

This progressive sentiment from the New Zealand government is hugely encouraging for indigenous rights activists and environmentalists worldwide but is still a highly radical exception among the settler colonial nations. Though it is still a far-flung dream to imagine the US ever expressing such historical remorse or desire to make amends, more than ever under the current administration, the legal move at Lake Erie is nevertheless a hugely encouraging step forwards in recognising man and nature’s interconnectivity.

Gerard Albert, chairman of the Whanganui tribal collective, welcomed the “recognition that the river is the indivisible and living whole of Maori understanding and not the fragmented, inanimate components… that has been the European approach.” This touches on the belief held not only by the Maori but by many indigenous groups worldwide, of the interconnected relationship between man and nature. One of mutual respect, obligation and responsibility and one gaining more mainstream attention across the western world. Thanks to Extinction Rebellion and other climate justice movements, this quasi-animist belief is, for the first time, gaining traction in the capitalist societies of the West. The significance of this cannot be understated. It is in great part the western belief, stemming from a particular Christian biblical interpretation, that nature is man’s dominion to shape and plunder as he so wishes that has led the world to the ecological brink.

It is still to be seen whether these new legal measures will hold up when challenged. They are yet to be tested in their respective legal system and may well prove toothless again conventional legal attacks. Indeed, it is not yet known the scope of the new move. For example, will a river be able to sue a corporation polluting its water with toxic waste? As yet, no one really knows. Only time will tell the true significance but what is for sure is that affording legal Personhood to nature is an innovative move worth trying in a world that requires protection as never before.

-

Legal2 years ago

Legal2 years agoHow we can defend and protect rights in the time of Coronavirus (COVID-19)

-

Legal2 years ago

Legal2 years agoLook at Afghanistan; why human rights are inextricably linked with the rule of law

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoThe right to protest in a Covid-19 era

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoA Public Health Approach to Tackling Racism

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoA Runaway Decision? Discussing and Defending R (Plan B Earth) v Secretary of State for Transport

-

Legal3 years ago

Legal3 years agoTrump: the most prolific execution President in over 130 years

-

Legal7 months ago

Legal7 months agoIs unjust enrichment really concerned with enrichments?

-

Economic3 years ago

Economic3 years agoWhat is the Rule of Law and What Difference Does it Make?